How school leaders can help educators navigate polarizing times

For educators and students, there is no such thing as “returning to normal” with the new school year. The COVID-19 pandemic, a divisive election, the shocking attack on the U.S. Capitol, and the stark reality of where we stand in matters of race have exposed deep fractures in our society.

Those fractures are exacerbated by virulent misinformation, leaving educators and administrators in a precarious position as they attempt to navigate this hyper-polarized climate. In response to requests for support in this area from district and school leaders, the Illinois Civics Hub at the DuPage Regional Office of Education did so with their webinar “Sorting Facts from Fiction: What Districts Can Do to Combat Misinformation in the Current Culture Wars” featured a panel of experts in social-emotional learning, civics education, school climate, and news literacy. The webinar, moderated by Darlene Ruscitti, regional superintendent of schools for DuPage County, explored proactive measures administrators can take to create a supportive school climate for all stakeholders. (If you missed it, you can access the recording here.)

Jonathan Cohen of the International Observatory for School Climate and Violence Prevention and Teachers College at Columbia University focused on the return to school, reminding participants to take time to acknowledge the difficult times we’ve been through. He stressed that being able to talk about controversial topics in a civil manner has never been more important — and that, in doing so, teachers can serve as living examples of thinking critically, grounding arguments in fact, and respecting another person’s view.

The pandemic has forced us to recognize the importance of emotion and reframe learning gains, said Maurice Elias, professor of psychology and director of Rutgers University’s Social-Emotional and Character Development Lab and co-director of Rutgers Collaborative Center for Community-Based Research and Service. He asked the audience to remember everyone has a COVID-19 story, and that some are emotionally powerful. While we all want to get back to normal, that is not possible unless we create a bridge through social-emotional learning and a positive school culture, he said.

Separating fact from fiction about civic learning and civics educators, Shawn Healy, senior director of state policy and action at iCivics, debunked common views, including one that civics teachers typically are liberals whose bias slants their instruction. However, research shows that teachers’ political beliefs often mirror their communities. But civics teachers are homogenous in some ways: they are disproportionally male and white. Healy acknowledged that parents and teachers want civics education to be emphasized more strongly, and they recognize its value in spurring young people to participate in democracy.

Building and demonstrating trust — among educators, administrators, and parents — is critically important in the current culture wars, said Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life. She noted that the terms we use to discuss controversial topics require careful consideration. When a shared understanding of a term is lacking — for example, with “critical race theory” — it’s important to take the time to understand what’s really happening and work to address those concerns.

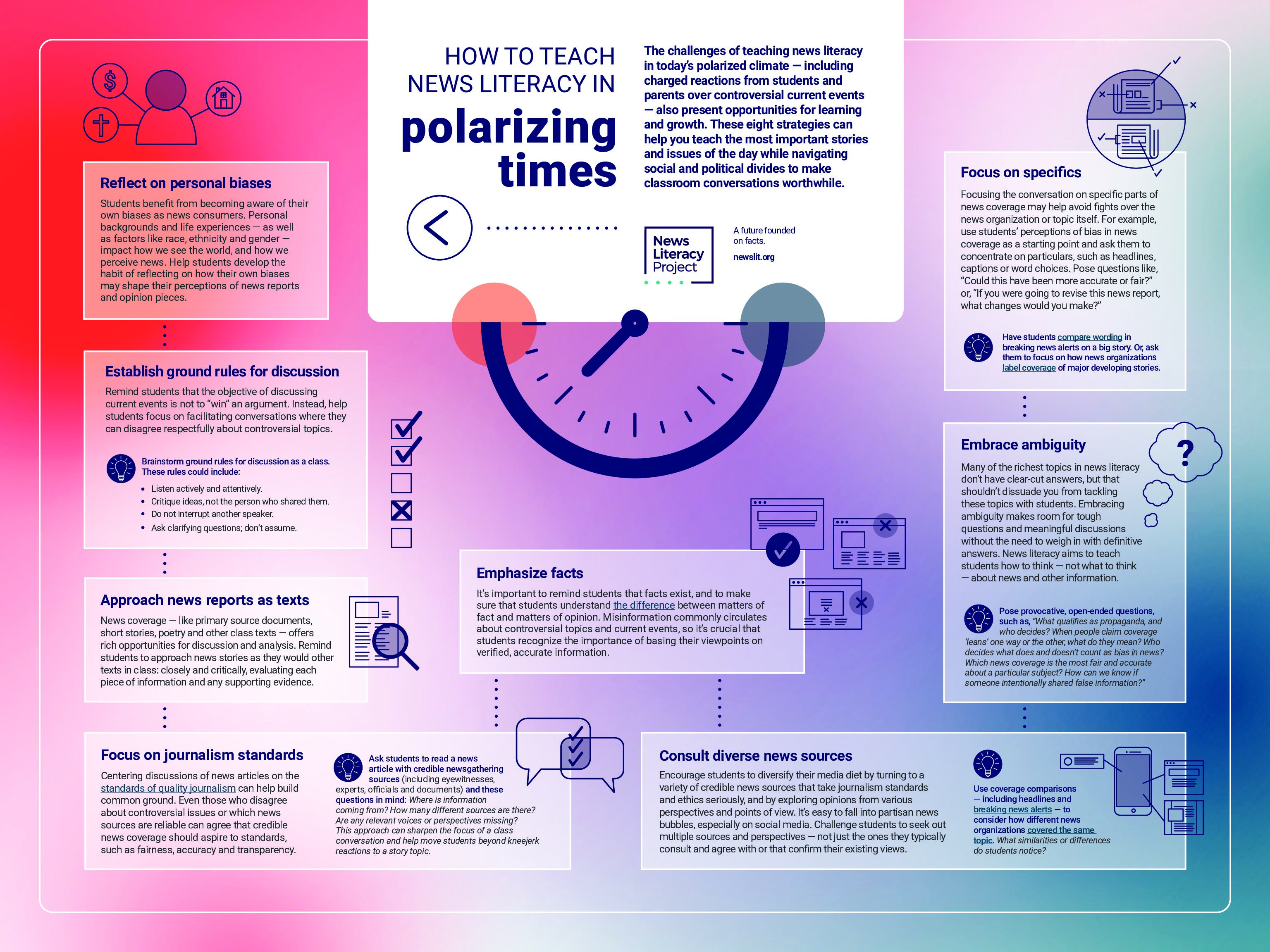

Peter Adams, senior vice president of education at the News Literacy Project, provided guidance to help educators teach news literacy in polarizing times. First, it’s important to establish ground rules for discussing controversial topics: Be specific and respectful; criticize ideas or positions, not people; engage in arguments, not fights, and be mindful of personal biases. He also pointed out the need for administrators to create a climate that values and accuracy and endorses facts — especially in a political climate in which extreme partisans and ideologues are pushing demonstrable falsehoods. Adams underscored the need for educators to help students learn news-literate dispositions — such as the ability to evaluate evidence, recognize fact-based statements vs. opinion-based statements, and be able to tell the difference between straight news and opinion journalism. He also discussed the importance of teaching students the standards of quality journalism and how to use them to evaluate the credibility of information in their daily lives.

Finally, he shared examples and resources from NLP that educators can use to engage misinformation and other news literacy topics in ways that sidestep partisan divides. Those resources include: ·

- How to speak up without starting a showdown (infographic)

- How to teach news literacy in polarizing times (infographic)

- Conspiratorial thinking lesson on NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom

- “Practicing Quality Journalism” lesson on Checkology

- NLP’s Informable mobile app

To learn more about resources and professional development opportunities with the News Literacy Project, contact Shaelynn Farnsworth, director of educator network expansion: sfarnsworth@newsit.org.

Participant questions, answered by NLP’s Peter Adams:

1. What are tools to deal with parents who have fallen down the rabbit hole and believe goofy things like Qanon and other false narratives? Are there certain culture war topics that are too toxic or unmanageable for secondary students?

- First, I think it’s important for teachers to understand exactly why some people fall for conspiracy theories. It’s a little like critical thinking gone haywire, fed by an intense desire to find explanations and reassurance for some of our most difficult problems. Our “Conspiratorial Thinking” lesson on Checkology explores why conspiracy theories often feel so compelling. Second, it’s also crucial that educators recognize that they may not be able to reason with people who have fallen deeply into these belief systems. Parents who are dabbling in conspiratorial narratives and ideas can likely be reasoned with if approached with a measure of empathy — but if you come across a parent who is a fervent believer of QAnon or vaccine conspiracy theories, there is likely little that a teacher can do to change their minds. In those cases, I think educators have to do their best to help the student avoid the same cognitive traps and civic disempowerment.

- And yes, some conspiracy topics are simply too toxic and graphic for teens. The QAnon delusion involves secret societies of pedophiles, for example, and that’s just not a topic you want to deal with in the classroom. Also, sometimes teaching students the details of a given conspiracy theory can actually backfire and make students vulnerable to getting drawn in. So, teachers really have to be careful. That’s largely why we focused our lesson on this subject on the mechanics of conspiratorial beliefs rather than on case studies of particular conspiracy theories.

2. I would have liked to have heard more suggestions about how districts respond to attacks/criticisms on social media about false information. Not everyone wants to engage in a conversation but someone can quickly repost or retweet inaccurate information posted on social media. I would like more information about Checkology too.

- This is a great question — and one for which there really are no easy answers. Our infographic, “How to speak up without starting a showdown,” gives some specific guidance on this question. But I think education officials and individual educators need to decide for themselves when it’s right to engage. Sometimes replying to an incendiary comment, particularly one designed to provoke outrage rather than reasoned debate, is best ignored. But when a post or comment spreads falsehoods that are acutely dangerous or harmful, I think it’s important to respond with links to accurate information. If people are resistant to links from well-known fact-checkers, you can always present the same evidence (e.g. the original of a photo presented in a false context) without disclosing where you got it. For more information on Checkology, definitely reach out to Shaelynn Farnsworth at sfarnsworth@newslit.org and she’ll answer all your questions.